March/April 2018

By Kent Kiser

Ringmills may lack the high profile of their flashier relatives, such as hammermill shredders and slow-speed, high-torque shredders, but their modest image belies their unique role in the scrap processing market. Ringmills, also called rolling ring crushers or rolling ring shredders, are designed to accomplish three tasks: reduce the size of infeed material, liberate commingled materials, and yield a uniformly sized product, all while generating minimal fines. Precisely how ringmills achieve those ends is what distinguishes them from their relatives and what keeps them in demand for certain applications, such as processing electronics, motors and meatballs, and other mixed nonferrous scrap.

Ringmills may lack the high profile of their flashier relatives, such as hammermill shredders and slow-speed, high-torque shredders, but their modest image belies their unique role in the scrap processing market. Ringmills, also called rolling ring crushers or rolling ring shredders, are designed to accomplish three tasks: reduce the size of infeed material, liberate commingled materials, and yield a uniformly sized product, all while generating minimal fines. Precisely how ringmills achieve those ends is what distinguishes them from their relatives and what keeps them in demand for certain applications, such as processing electronics, motors and meatballs, and other mixed nonferrous scrap.

Lord of the Rings

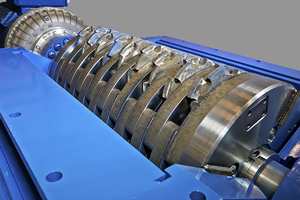

Ringmills differ from other crushers and shredders because, as their name implies, they use rings rather than hammers or knives to process material. Most scrap processing applications use rings that are metal disks with evenly spaced, squared-off teeth around the outer rim. The number of teeth depends on the size of the ring, but some have 10 or more. (Other industries use ringmills with smooth rings to process friable material, such as ceramic or aggregate.)

A ringmill rotor typically contains four ring shafts, each containing multiple rings and gap spacers across the width of the shaft. Seven to 12 rings per shaft is typical for a midsized ringmill, manufacturers and sellers say, but the number varies based on the unit’s size. The rings on one shaft align with the spacers on the adjacent shafts to ensure complete processing coverage across the width of the machine.

A ring’s mounting hole is two to two-and-a-half times the diameter of the shaft on which it’s mounted, allowing the ring to deflect and spin 360 degrees, creating a ripping action. During operation, each ring rotates freely on the shaft, with centrifugal force holding the ring teeth outward. The rings hit incoming material, deflect, and rotate upon impact and—in the process—crush, shred, and liberate the material without generating a lot of fines.

It’s important to “make sure the rings have sufficient size and mass to cut their way through the infeed material and not just deflect out of the way,” says Mike Laskowsky, Northeast regional sales manager for Williams Patent Crusher & Pulverizer Co. (St. Louis). If the material doesn’t get reduced immediately, it will recirculate inside the processing chamber, which generates heat and wears the rings and internal components faster. “Every time you hit material, that imparts energy to it, and that energy translates into heat,” he says. While some recirculation of material is inevitable, the goal is to minimize the amount.

The Milling Process

As scrap enters a ringmill, the rings drive the material against a breaker plate. The material proceeds to the lower housing, which has a series of grates or screens to help liberate and size the material. Recyclers can choose grates or screens with openings of different sizes and configurations depending on the material being processed, says Skip Anthony, vice president of sales and service for American Pulverizer Co. (St. Louis). When processing material with small pieces such as turnings, for example, the openings could be as small as ¼ inch, but typically they fall in the 2- to 4-inch range. “The smaller the grates, the lower your throughput, so don’t make the size any smaller than you have to,” says Rustin Ross, president of Alan Ross Machinery Corp. (Northbrook, Ill.), which sells recycling-related processing, sorting, and handling equipment. In terms of shape and configuration, the holes can be square, rectangular, or round, and they can be arranged in line or staggered, depending on the infeed material and the desired finished product.

Material that doesn’t discharge through the lower housing continues around to the unit’s rounded upper back housing, which has wear-resistant liners, and recirculates through the mill’s input area. After passing through the mill one or more times, the scrap is small enough to pass through the bottom grate openings. From there, it can proceed through various downstream sorting systems, which can include magnets, eddy-current nonferrous separators, sensor sorters, and more.

If an unshreddable item enters the processing chamber, the rings’ ability to deflect upon impact minimizes wear on them and prevents them from getting damaged. Ringmill manufacturers offer different approaches to handling such tramp elements. In one design, the tramp item—which passes through the ringmill with more ballistic velocity than lighter material—ricochets off deflector plates on the infeed hopper, goes over an internal kick plate, and drops down a reject chute into a bin next to the machine. “The tramp material is like a cue ball, banking off those plates and then being extracted that way,” Anthony says. Other ringmills feature a trap compartment in the back of the processing chamber. After a tramp element pinballs inside the mill for a while, it finds its way into this compartment and remains there until the operator removes it during maintenance. “We like this method,” Laskowsky says, “because it’s very simple—there are no moving parts—and it forces people to make a periodic inspection of the equipment.” Still other ringmill models have a reject door with a counterweight that gives way under a certain amount of force so the tramp metal can exit, Ross notes.

Flexibility and Durability

Recyclers turn to ringmills, in part, because they’re flexible, able to size-reduce and liberate an array of scrap materials, including turnings, end-of-life electronics, light-gauge steel, small electric motors and meatballs, irony aluminum, nonferrous shredder pickings, and transformers. A ringmill’s “properties as an impact mill suit some applications really well,” Ross says. When processing electric motors, for instance, the rings break away the outer steel shell and further liberate and reduce the inner nonferrous components. “It’s important that the [motor] is being opened instead of being compacted,” says Carsten Nielsen, technical support/area sales manager for Eldan Recycling (Faaborg, Denmark). When the processed material exits the mill, magnets can remove the steel and then “the high-value material can be further processed,” he notes.

In a typical processing scenario for electronics, incoming material undergoes initial size reduction in a slow-speed, high-torque shredder, then a ringmill liberates the different elements and processes the material to a final size for downstream separation. “The shredder reduces material size but leaves it commingled,” says Adam Shine, vice president of Sunnking (Brockport, N.Y.), which processes e-scrap through a slow-speed shredder/ringmill combination line. “The ringmill does a nice job cleaning up that material.”

When processing turnings, a ringmill reduces them to a smaller, consistent size for greater density, easier briquetting, and better fluid recovery. “A shear-type shredder doesn’t give you the same consistency in size as a ringmill,” Anthony says. “Shear shredders also can enclose materials inside processed pieces, which can create problems further down the line.”

Ringmills also are flexible in several mechanical ways, notes Rafael Reveles, president of Converge Engineering (Roseville, Calif.), a recycling equipment integrator. For example, users can replace some of the machine’s rings with hammers to get “a little more fragmenting along with liberation,” he says. If the unit is belt-driven, the operator can change the size of the pulley diameter and, in the process, change the rotor speed in the mill, Reveles says. And, of course, the machines can accommodate a variety of grates and screens with different hole sizes and configurations. “It’s a highly flexible platform,” he says.

Another major ringmill selling point is its durability. Most ringmill rings are made of manganese steel, which means they work-harden and are wear-resistant. The rings are reversible, giving them double the wear life. Also, because they deflect, they don’t take the same pounding as hammermill hammers, sellers say. The numerous teeth on each ring also extend the ring’s wear life “because we’re not trying to do all the processing with one edge,” Anthony says. With replaceable grates, liners, and rings, Nielsen calls a ringmill a “virtually indestructible machine.”

Of course, a ringmill’s durability depends on how well you use and care for it. “The life span of this equipment is long but highly correlated to how well it’s maintained,” Ross says. For example, if you only feed material across half the machine—not uniformly across the width of the rotor—you will need to replace the rings in that section more frequently. It’s also crucial to monitor the wear on the internal components and change them as necessary. “Your wear plates are there for a reason,” Ross says. “If you aren’t changing them frequently, then the machine is going to take the wear instead of the wear plates.” Reveles says he has seen ringmills with holes worn through the mill. “If you aren’t on top of changing your liners and wear plates, you’re going to put a hole through your machine pretty fast,” he states. Depending on the application, it also can make a difference whether your liners are cast or cut from plate alloys. “Match your wear plates to the job you’re doing,” Reveles says.

If you inspect the machine regularly and pay attention to how parts are wearing, a ringmill will be “a very reliable piece of equipment,” Laskowsky says. How reliable? “We get parts requests for machines built before World War I,” he states.

Price and Selection

Manufacturers tout ringmills’ competitive price tag compared with other processing equipment and the quick return on investment. “It’s an affordable piece of equipment that really does a nice job of separation,” Shine says. One caveat when soliciting prices, however, is that there’s no standard ringmill setup. “Each one is a custom piece of machinery that’s tailored to meet the needs of that specific application,” Laskowsky says. Even so, he ventures that smaller ringmills can cost $30,000 to $40,000, while the largest units can run more than $500,000. The price tag also depends on the components the system includes, such as an infeed conveyor, undermill shaker table, takeaway conveyor, and downstream separation equipment. Even with such price variability, “a lot of customers are pleasantly surprised when they find out what the machine can do and then what it costs,” Anthony says. To minimize the purchase price, there’s always the option to buy a refurbished machine, as Sunnking did. “That was a good way to get our feet wet with a ringmill without overcapitalizing,” Shine says.

On the ROI question, manufacturers say the return depends on the material being processed and the throughput capacity. Even so, ringmills generally offer a quick return, Anthony says, because they “are being used to get final recovery of materials that have value but that need further processing to get a higher percentage of recovery.”

If you’re in the market for a ringmill, realize that those used for scrap processing are different from those used to process coal and other friable material, and “it’s easy to be confused between the two,” Ross says. “A coal-style ringmill is not suitable for scrap. That’s the first thing you want to avoid—buying the wrong type of ringmill.” Adding other words of caution, Ross points out that ringmills can be loud during operation, are energy-intensive, and can generate a lot of dust. You can minimize dust concerns by using a water-injection system in the mill or a cyclone dust-collection system depending on the material processed, Reveles says. He also recommends monitoring the ringmill’s temperature during operation to make sure it isn’t getting too hot, especially when processing metal. Vibration is another concern; isolation mounts on the machine can address it, he adds. Shine offers one more piece of advice: Feed material into a ringmill “at a continuous but not aggressive rate. It needs to be a little bit metered. If you try jamming too much material into it, then you could potentially do some damage there.”

Make sure the equipment is the correct size for what you’re planning to process, Anthony suggests. “Don’t be forced into buying a machine that’s overkill, but don’t go for the low end, either, because you’ll only cause yourself ongoing operating problems in the future,” he says. Fortunately, ringmills come in a wide array of sizes, so you can buy a slightly larger unit without increasing the cost of the machine significantly.

A ringmill’s size often is expressed in terms of its rotor diameter, with the most common range from 20 to 48 inches. Which size is right “depends on what material the customer is running and how many tons per hour they want to process,” Anthony says. The rotor’s width varies as well, with Laskowsky saying “a rule of thumb is, ideally, to stick to a square arrangement”—that is, with the width matching the rotor diameter—though it’s OK for the width to go up to twice the diameter size. “If you go wider than that, you run the risk of bending a shaft more easily if a large, uncrushable object gets thrown into the center,” he says. “That’s why you keep the width as narrow as possible.”

An electric motor—ranging from 75 to 3,000 hp or more for the largest units—drives the ringmill’s rotor, with power drawn from 480-volt AC electricity or belts. “A belt-driven machine is going to be more forgiving of a jam,” Ross says, “because the belt can slip, whereas the direct drive of the motor will be forced to stall. So that’s a consideration.”

The ideal motor horsepower depends on the specific application. “The same size machine could require different connective horsepower to process different materials and meet certain finished product requirements,” Laskowsky says. Producing a coarse finished product, for example, is less demanding on the machine, so it doesn’t require as much horsepower. Conversely, producing a fine grind requires more energy to reduce the material, which dictates a larger motor.

Although the rotor speed depends on the rotor’s diameter, most operate in the range of 600 to 1,200 rpm. As Anthony notes, a ringmill is “a medium-speed machine—not as fast as a hammermill, but much faster than a slow-speed, high-torque shredder.” The throughput capacity also varies based on the size of the unit and the type of input material, with the range spanning 500 pounds to 35 tons an hour.

Consider a unit’s maintenance features before buying, such as how easy it is to open the mill, remove the rotor, and change the rings, grates, and liners. “Some mills can be hard to open,” Reveles says, “and make sure you know how you’ll lift out parts like the rotor because they’re heavy.” It’s also a good idea to ask the ringmill manufacturer to run a sample of your material to show you what the equipment can do. “I never recommend buying any size-reduction equipment without doing a test and knowing how it will perform,” Reveles says. If a manufacturer can’t or won’t conduct such tests, you can take that into consideration in your buying decision. One final factor to keep in mind is whether the vendor offers a good selection of spare parts, especially cast parts. Since castings can take a long time to get from the foundry, “you want to make sure the manufacturer has parts on the shelf so they’re available when you need them,” Reveles says.

Although the popularity of ringmills—like all scrap processing equipment—ebbs and flows, Ross says, the equipment has established a secure market niche. China’s recent moves to tighten quality standards for imported scrap are giving ringmills a boost, Anthony adds. Those standards have “pushed recyclers to look at what else they can do to get the highest recovery from their material, increase its profitability, and not have to rely on someone else to keep that market going,” he says. “Everybody wants to get everything out of their material now.”

Kent Kiser is publisher of Scrap and assistant vice president of industry communications for ISRI.

For size reduction and liberating mixed materials, ringmills have long been the secret weapon of recyclers in certain processing niches. The imperative to reduce contamination has the potential to increase their popularity even more.